Interview with Orde Eliason

The impact of a great teacher goes beyond classroom or lecture theatre and can inspire you for life.

Step forward, one of my early role models. South African-born photojournalist Orde Eliason (above). In the 1980s, Orde was a visiting lecturer on my degree course at Leicester’s De Montfort University. He later established the Link Photography Agency.

In the days before the Equalities Act and Disabled Students Allowance (DSA) when there was zero communication support for deaf students like me, Orde’s inclusiveness and humour hugely inspired me.

After uni we went in different directions, as you do. In 2023 social media reconnected us, as it does. So, 40 years later, ahead of my return next month to De Montfort University’s gallery to exhibit Deaf Mosaic, I reached out to Orde to catch up.

SI: As I’ve made photographs now for 50+ years, it’s been one of the few constants in my life. In the 1960s, I made images as a kid with my Kodak Brownie. And here I am in 2024 still doing it – albeit with a Nikon these days.

As a born-deaf child, I often felt excluded at school and in large family or public gatherings. So, I stood back and became an ‘observer’ - of people, of situations. Later, this leant itself naturally to making photographs. Its stuck with me ever since. How about you? Any thoughts as to deep down why you’ve been a lifelong photographer?

OE: In a similar vein to you I too have been taking pictures since I was 6. My first camera was a Kodak Instamatic. My local nickname was “Die Weglooper” - the one who wanders (walks away). True to form I’ve always been curious about what people get up to. During visits to Johannesburg, the equivalent to Manhattan compared to my childhood home in Windhoek, Namibia, I’d awake around 05.00 am and roam the streets. As a kid with a camera no one hindered my progress.

SI: Okay, so in 1976, you left your comfort zone and came all the way here to England and find your niche as a photographer. What compelled you to go half way around the world to do this?

OE: South Africa, like many places, is a land full of contradictions. At that stage, it was a cauldron of prejudice with many layers of exclusion. During my National Service (conscription) in the air force, I went to photography school at nights. My decision to study in the UK was influenced by education and politics. Gaining insight into my characteristics, there was a good chance that if I remained in SA I would tangle with the authorities.

Ward End Park, Birmingham (1979)

SI: In one of your earliest photo projects – Saltley Stories – you documented Birmingham’s diverse white-black-Asian working class (above). It reminds me a little of the work I do today for Deaf Mosaic – exploring diversity within the UK deaf community. It takes chutzpah to approach people from different backgrounds and cultures. Did that come naturally to you or was it a skill that you had to learn?

OE: Being a stranger in a foreign land is a dual-edged sword. You either sink or swim. By exploring Birmingham on foot and bus, access to this sprawling city became accessible to me.

Hurst Street cafe, Birmingham (1980)

OE: Simply by watching people, being intrigued by them, employing some guile and sheer chutzpah you appreciate that in many cases most people are equally curious as to what’s this stranger up to? As you can see in the Hurst Street cafe photo above. It’s a combination of intrinsic curiosity and a realisation that you aren’t going to get interesting images unless you are there. It isn’t going to happen if you don’t get up out of your seat and just go there.

Festival of the Vine Paarl, South Africa (1984)

SI: One of the things I recall about you at uni, was feeling excited by the adventure stories you told us students about your assignments in Namibia and South Africa and the occasionally risky situations that you might get exposed to. How did you handle that? Getting the photo and staying safe? I was deeply moved by the above photo of an all-white majorette display where one of the black bystanders suddenly joins in the march too.

OE: In many of these situations you have to draw on all your wits and swiftly (intuitively) react. Humour, knowledge, language, playing dumb, genuine interest but mostly being sincere usually gets you through.

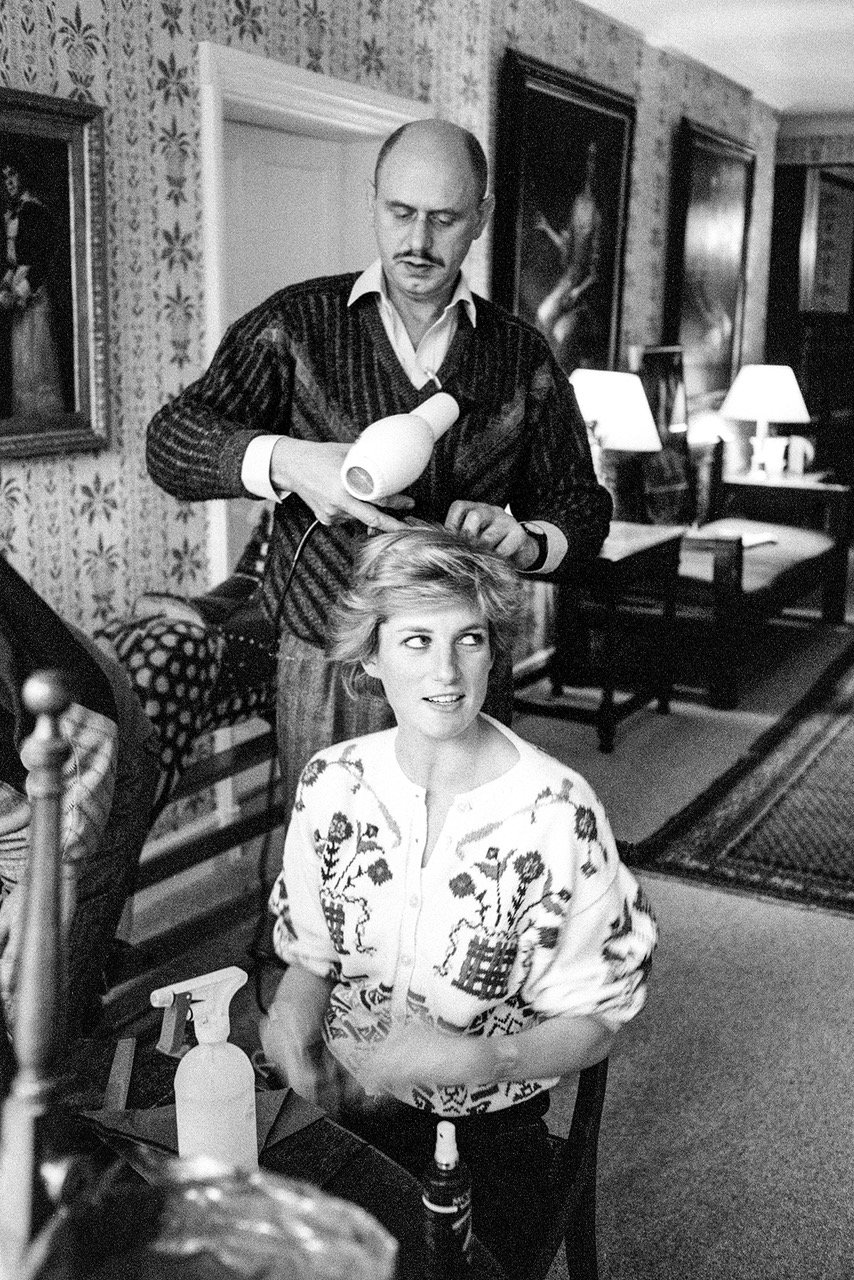

Princess Diana having her hair done, Hereford (1988).

SI: You’ve photographed so many interesting people – from Brian Eno to Nelson Mandela to Princess Diana under a hair-dryer (above). For you, what for you makes a good portrait?

OE: By observing the individual and gauging what their attention span can tolerate. Many pressures known and unknown swirl in their heads. Aim to engage the sitter to dispel the idea that you are a threat (real or perceived). Then rely on your instinct to grab the moment. Or, it may be a more controlled situation where you can collaborate.

SI: When I think back to our uni days, it’s incredible how photography has evolved since. Think of all those hours we spent in darkrooms under a red ceiling light with film canisters and sulphuric chemicals. I’m sure none of us saw a future where photographs would be made digitally and processed on computers. What’s your view on film vs. digital? Pros and cons?

OE: I have enjoyed the magic of the chemical days where the processing side allowed many a good hour thinking, dreaming, listening to new music before returning to reality outside the darkrooms. Nowadays, the benefits of digital advances is remarkable. The explosion of having to acquire multi-disciplinary skills can be frustrating with regular hardware and software upgrades. Yet, the new digital frontiers cater to so many different interests making it a godsend. Each route has its merits.

SI: At uni, I read how in the 1830s after Fox Talbot ‘invented’ photography that traditional artists, with their paintbrush and canvas, were outraged it would make their work extinct. And yet 190 years later, painting is still with us. Now with the emergence of Artificial Intelligence (AI), people are complaining that it will ‘kill’ photography. What’s your take on this?

OE: I doubt that it will “kill“ photography. Continuing with the previous train of logic, a new discipline opens and allows fresh possibilities in the right hands. Certainly, passionate debates will ensue and a spate of new imagery will emerge. The issue of control, manipulation of our attitudes are probably more important for us to internalise so we can arrive at our own standpoint about it.

Nelson Mandela, Harare, Zimbabwe (1991).

SI: Okay, so this May I’m flying out to Uzbekistan to do some photography with the deaf community out there. For 70 years under Soviet control with closed borders, Uzbekistan was a mystery to the rest of the world. Now opening up to the west. It’s a bit of a leap into the unknown for me, like you’ve done so often before. So, what’s your advice? Do’s and don’ts?

OE: You’re very well-equipped already by having demonstrated the exciting imagery that you make for Deaf Mosaic. You have sign language skills, you’re organised and enthusiastic. Learning a few key phrases always makes for pleasant surprises. Read about their culture and situation. Get a little fitter than normal. Anticipate a few (technical) scenarios which might go wrong and prepare solutions by taking a few spares (cables, adapters, batteries). A supply of your favourite nutritional snacks in case. Lastly, have a great adventure and enjoy your time there. We will all look forward to seeing your results. Bon Voyage!

SI: That’s great advice, as always. Many thanks, it’s great to catch up with you, Orde. We’ll keep in touch.

To enjoy more of Orde Eliason’s photography, visit these sites.

Orde Eliason’s Link Photography Agency

Orde Eliason and Saltley Stories

Orde’s Instagram